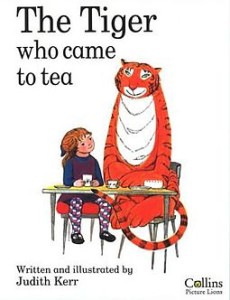

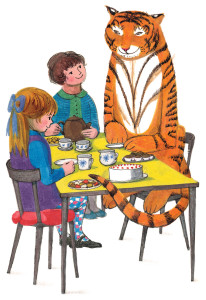

Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea

After rereading Judith Kerr’s Bombs on Aunt Dainty, a very autobiographical novel that describes her first art classes, I decided it was high time I should read some of her self-illustrated picture books. And it turns out that, although Kerr is less well known in the U.S. than in the U.K., her picture books are MUCH more available in the U.S. than her more recent novels. So I have her great classic, The Tiger Who Came to Tea on the table next to me as I’m writing this.

It’s no surprise to me that this book, first published in 1968, has sold over two million copies. The only thing that surprises me is that I never came across it before.

It’s the kind of book that makes you feel that you have read it before. It feels absolutely archetypal—like exactly the story a very young child would want to hear. From the surprise arrival of a friendly tiger who eats up all the food in the house, to the wish-fulfillment of the ending—going out to dinner wearing pajamas and eating delicious sausages and chips and ice cream—it is a perfect picture book.

It’s an entirely comforting and safe and happy world, with just a frisson of excitement—and I love seeing that Judith Kerr could imagine and create that kind of world for her own children after fleeing Hitler’s Germany in her own childhood. The only potentially scary thing that comes knocking at the door here is a tiger—and he turns out to be very friendly tiger, who is only hungry for sandwiches and buns, not people.

It’s the kind of book that makes me wish I had known about it when my daughter was about 1-4, as I know she would have loved it. It’s also the kind of book that makes me immediately think about who I could give it to. But that’s actually where I was stopped a bit short.

As it happens, there’s no father in each of the two families I immediately thought of buying the book for. One is a family with two mothers and the other is a family with a single mother. And it didn’t feel just right for them, because the mother in the story (obviously drawn to look like Judith Kerr as a young mother, as readers of When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit will recognize) is a bit ditzy and childlike. The mother has a charming, close bond with Sophie, but when the tiger eats up all the food, she can’t think of what to do until Daddy comes home.

That’s not very much of a problem, I think—it’s a bit of gentle self-mockery on Kerr’s part, combined with the traditional gender roles of the 1960s—and I’d read it to my own child or (if I had one) pre-K classroom explaining those things. Or I might say, “On another day, maybe Daddy will stay home with Sophie while Mummy goes to work—and what animal do you think will come to tea then?”

But even so, it didn’t seem like the right book to give to the two families I had in mind. I didn’t balk at the idea of giving them a book with both a father and a mother, because lots of families are like that, but I didn’t want to choose one where the father solves the problem that the mother doesn’t seem able to.

Too bad. But Judith Kerr, if you felt so inclined, maybe it’s time for a companion volume to this lovely, archetypal book. What animal will knock on the door while Daddy is home having tea with Sophie? And what will Mummy do to fix things when she gets home?

02/20/2017 at 9:21 pm

I adore Judith Kerr’s work. Thanks for highlighting this book, Susan.