Laura Amy Schlitz’s The Hired Girl, Jews, and Baltimore Schools

I’ve just been reading Laura Amy Schlitz’s The Hired Girl (Candlewick 2015) with great pleasure. It has a compelling plot, it gives us a glimpse into Jewish life in turn-of-the-century Baltimore, and Joan is such a terrific character—an utterly believable, impulsive, romantic, imperfect, likable fourteen-year girl. And how often can a character be found reading my favorite George Eliot novel, Daniel Deronda, in any book—let alone in a children’s book?

I grew up in Baltimore, and reading this novel set off a series of questions in my mind about the city in the early twentieth century. I paid close attention to the place references in the novel, such as Enoch Pratt Free Library, where Joan teaches little Oskar to read. (That’s where my family used to go on weekends for storytime!)

So when the novel ends with Joan attending an innovative new school located on a street with a name it seemed to me that nobody could possibly make up—Auchentoroly Terrace—I just had to go to my computer to see if Laura Amy Schlitz’s writing mind works in the same way mine does. Could this unnamed school just possibly be the Park School where Schlitz is a librarian and teacher?

I had a strong hunch it was—and BINGO! That was the first address of the Park School when it opened in 1912! In Joan Skraggs, Schlitz has imagined one of the earliest students at the school.

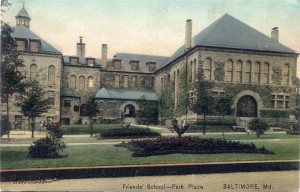

But that connection with the Park School made me worry about an earlier passage in the novel–about an unnamed Quaker school. When I was a child, I was for a while a scholarship student at Friends School in Baltimore. It was a very progressive school, and I received an excellent education there. I remain deeply appreciative of that scholarship. I look back on those years, until Friends could no longer afford to fund the scholarships for me and my many siblings, as among the happiest of my long educational career.

When I was at Friends School, there were a lot of other Jews. Although it was a Quaker school, I remember only one Quaker in my grade. When our kindergarten class put on a Christmas pageant, the girl originally chosen to play Mary pulled out because her parents thought it wasn’t appropriate for their Jewish daughter. I got put into the role next. We weren’t Christians either, but I guess that didn’t bother my parents. So I played Mary, holding a flashlight wrapped up in a blanket to represent the baby Jesus! I remember my father—or was it my older brother David?—making jokes about turning it on to create a halo! Jews had a definite presence at Friends in my childhood.

But in The Hired Girl, a Quaker school in Baltimore has educated the older two Rosenbach brothers but has refused to accept Mimi, the third child as a student, because they have too many Jews. They’ll only take her if the parents pay an extra fee of $10,000 to the school!

Well, how many Quaker schools are there in Baltimore? Could Schlitz possibly be basing this on something that happened at Friends School in the early twentieth century, I worried? Could that have been MY SCHOOL? This seemed very much at odds with the Friends School I knew in the 1960s and 1970s.

I’m afraid it looks as this moment in the novel was at least to some extent based on Friends School history. A bit more internet sleuthing reveals that Friends School had a high proportion of Jews in 1899, when it opened, due to its proximity to the Jewish neighborhood of Eutaw Place, where Joan finds her live-in position with the Rosenbach family. But by World War I, Jewish enrollment had sharply declined.

It isn’t clear from what I’ve come across in a quick search that there was a Jewish quota exactly, or that extra pay was demanded from Jews—but the headmaster at the time was pleased when the number of Jews dropped off.

Jews at Friends School pre-World War I

Is there more to the story? Maybe I’ll email Laura Amy Schlitz to see if this is based on a more particular incident at Friends School. Stay tuned.

02/05/2016 at 6:54 am

The halo joke might have been mine, or I might have been repeating it from the previous year when I played Joseph in the kindergarten Christmas pageant. I had forgotten that it became a tradition to have Meyers playing parents of Jesus at Friends School!

With respect to the number of Jewish students in the 1960s & 1970s (“turn of the century” can now refer to 2000 rather than 1900!), I remember there being 6 in my class (not counting me, of course) one year when we self identified for some class discussion, i.e., somewhere in the 25%-30% range. (And also only one or two Quakers.)

02/14/2016 at 10:02 pm

David’s comment above is so funny! You Meyers had a nice tradition going there. The potential Jewish quota at your school doesn’t surprise me much, unfortunately. That stuff definitely happened—at the college level too. Often it wasn’t explicit. Now many people have argued convincingly that it’s happening with Asian American students at some schools. Who knows. Schools’ admissions procedures will always be inscrutable, and often kind of crazy.

Good job with the blog so far: great range of topics!

02/14/2016 at 10:12 pm

I really doubt that Friends School had Jewish quota when I was a student there, but they seem to have had some such inclination at an earlier moment in history. Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where I went to college, didn’t have a great history in that regard either, although quotas weren’t any longer in place. But my husband, who is some years older than I am, applied to Johns Hopkins and didn’t get in. At his interview he was asked if his surname was Jewish.

02/15/2016 at 7:19 am

I didn’t know that! Was that for undergraduate school, or graduate school?

02/15/2016 at 3:50 pm

He was applying to Hopkins as an undergraduate. That would have been about seven years before you attended. Let’s hope it was because of a rogue admissions officer. But Hopkins did once have a Jewish quota, and he was coming from Bronx Science with a Jewish name and appearance. And, you know, he has now become a professor at Yale. It does seem likely that as a teenager he was, as they say, Hopkins material.

02/15/2016 at 12:28 am

My grandparents felt that the person who interviewed my uncle at Harvard hated him because they could tell he was Jewish. I didn’t think they necessarily would have known, but my mother is sure they did. I think it was pretty obvious with my grandfather in particular. I mean… who knows. But this stuff was documented during that time. Interesting re: your husband.

02/15/2016 at 3:53 pm

My father, who was not at all prone to seeing antisemitism everywhere, was absolutely sure that he wasn’t admitted to MIT as an undergraduate in the late 1940s because he was Jewish. The fact that he later became a distinguished mathematician does seem to make his interpretation probable.

02/15/2016 at 4:03 pm

Of course, places like MIT are (and were even then) so selective that it’s impossible to say for sure. But it seems very likely that he would have gotten in without that strike. MIT is different from many schools in that math/science talent is by far their biggest priority, and I’m sure your father showed those talents pretty clearly. How fabulous that he wasn’t one to see anti-Semitism everywhere, given what he went through. My family was never big on looking for it, and at times my mother actually got annoyed with people who had eagle eyes for it where it probably wasn’t there (like the woman who was up in arms over the Christmas songs at my elementary school).

I was just talking to my brother about this topic. We could both only think of a few times where we felt anti-Semitism. He had one fairly big case: my cases were just little things.

02/15/2016 at 8:17 pm

Sadly, my daughter has already run into a fair amount of it. But I think that’s one of the most insidious things about prejudice. It’s often subtle. So it can make people who believe they perceive it seem paranoid. My father always said told us that we had to be much better than just as good as other people to get something. His feeling was that we should just assume this and always aim much higher than being equally good. I was interested in reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’s BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME to find that he was taught something very similar as a child. Also, check out this book, TWICE AS GOOD: THE STORY OF WILLIAM POWELL AND CLEARVIEW by Richard Michelson, illustrated by Eric Velasquez. Richard Michelson website

02/15/2016 at 10:44 pm

What a shame that your daughter has experienced so much of this. I actually thought of a few more examples after I finished writing my last comment. It does exist, and for sure sometimes it’s subtle.

Fascinating that your father told you you had to be far better than others to get the same reward. That was because you were Jews? You know… I once had an experience with my mother that could be related. She was upset with me because she didn’t like my attitude about something in school. And I said something like: “The average person doesn’t work that hard.” And she kept bothering me about it for days, how the average person isn’t very impressive, and how sad if I was only reaching as high as the average person, etc. It really cracked me up, but also got me thinking. Maybe she had internalized something along the lines you mention: who knows.

02/16/2016 at 2:37 am

Could well be. I wonder if she would remember.

02/25/2016 at 3:43 am

I have alluded to that comment recently: she knows I remember her saying this even if she doesn’t. I’m going to ask her….