For Readers of Skating with the Statue of Liberty: the Double V Campaign

The Double V Campaign

A Guest Post by Educator Catherine Maryse Anderson

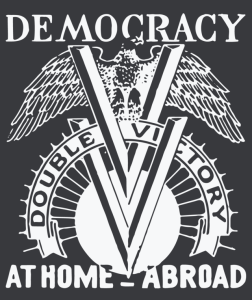

Today we are surrounded by logos and slogans designed to capture our attention, draw us to a product, or encourage our participation in a group or movement. Shoes and other items of clothing often have a symbol instead of a name, and phrases like “Yes We Can” or “Kinder Gentler Nation” are associated with presidential campaigns.

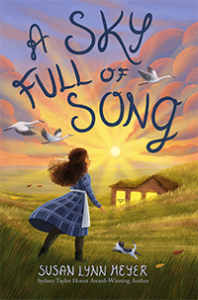

In Skating with the Statue of Liberty, we learn about the Double V through September Rose and her brother, Alan. The Double V as a symbol and slogan was started in 1942 by the , one of the era’s most prominent African American Newspapers, also known as “The Black Press.” Regional and national newspapers today feature stories about all the people in the region and the country, but in 1942, the United States was still a very segregated country. As a result, African American communities relied on the Black Press to ensure their news was told and shared.

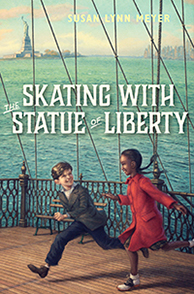

In World War II, great numbers of African Americans were asked to fight for freedom against the “Axis of Evil” abroad, only to return home to a country still very much in the grips of fundamentally racist Jim Crow-era beliefs. Despite risking their lives for this country, when they returned home, they did not have the ability to make the same kinds of choices about their lives as their fellow white soldiers did. In the spirit of naming this bind, and trying to help African Americans write themselves into their country’s history in a patriotic and emboldened way, James G. Thompson, a 26-year-old African American man, introduced the Double V concept in a letter to the editor of the Pittsburgh Courier. His voice is considered one of the main sparks of the Double V campaign.

In it, Thompson wrote: “Being an American of dark complexion and some 26 years, these questions flash through my mind: ‘Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?’ ‘Will things be better for the next generation in the peace to follow?’ ‘The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries, which are fighting for victory…Let we colored Americans adopt the double V for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within.” —James G. Thompson, 1942, Source: Learner.org

[Historical Note: The term “African American” was not used to describe people of color until the 1970s. In the 1940s, Black people most often described themselves as “Negro” or as “colored.”]

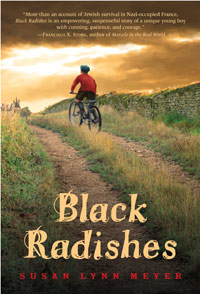

Shortly thereafter, other African American newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, The Baltimore Afro-American, and The New Amsterdam in New York City carried stories brought into focus by the Double V campaign. Stories expressed outrage about the treatment of African American soldiers abroad and citizens at home.

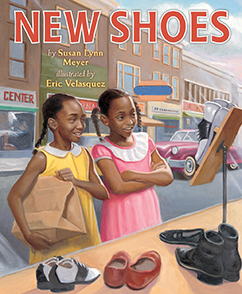

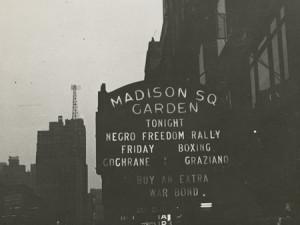

The Double V campaign aimed to change the way African American soldiers were seen and celebrated both at home and abroad. Each week Black Press newspapers featuring the Double V image would relate stories about African American war heroes and African American war effort volunteers at home and would encourage readers to buy war bonds. Often papers included endorsements by political figures and celebrities to call more attention to the cause. Double V Clubs were formed to gather items to send to soldiers overseas; to meet with businessmen about nondiscriminatory hiring practices; and when conversation failed, to organize demonstrations, as Alan and his contemporaries did in Skating with the Statue of Liberty. But on the other side of this was a growing frustration that not enough was being done fast enough. Tension in African American communities began to mount, leading to large-scale riots in Chicago and New York.

Interestingly, the Black Press was often caught in the middle, fearing that if they did not condemn the riots or protests, then all African Americans might be seen as taking away attention and resources from the United States to defeat of the Axis powers abroad. But what the Double V campaign gave way to was a deepened sense of purpose and voice in many communities, leading to Freedom Rallies in the late forties and several long-term changes, like the breaking of the color barrier in sports like baseball in 1947 with Jackie Robinson and President Truman’s Executive Order to desegregate the Armed Forces in July, 1948.

What is a cause or movement that you believe deeply in? What was it about the slogans or logos they employed that caught your attention or helped you to understand their message?

What is it about the Double V campaign that may have particularly appealed to Alan in Skating with the Statue of Liberty? What is it about being part of this movement that might have felt dangerous to September Rose’s grandmother? Have you ever wanted to participate in a cause or movement that someone else did not want you to be part of? How did you handle that? Do you think Alan made the right choice?

Additional Educator Resources:

TeachNYPL: World War II and the Double V Campaign (Gr. 10-12)

Sources:

“The Double V Campaign in NYC” by Hannah Lee, The History of NYC

“What Was Black America’s Double War?” by Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Root

“Democracy: Double Victory at Home-Abroad,” American History in the Making

“The Tuskegee Airmen at a Glance,” The National WWII Museum: New Orleans

Image Sources:

Image 1: Double V Logo (Source: Inquires Journal)

Image 2: WWII Propaganda Poster (Source: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans)

Image 3: Participants in the Double V Campaign (Source: National Archives)

Image 4: The Inkspots Promote Double V (Source: Memorial Hall Museum’s American Centuries)

Image 5: The Double V Campaign in NYC (Source: The History of NYC)

About the Educator:

Catherine Maryse Anderson has an extensive 15-year background as a public school literacy and humanities teacher in Portland, Maine. She spent two years as a literacy coach for Portland Public Schools and led statewide symposiums on building educator capacity for cross-cultural competency in the classroom from early childcare through college. She was a runner up for the Teaching Tolerance Educator of the Year. Catherine has been involved in ongoing performing arts projects for twenty years and is a published poet and essayist.