For Readers of Skating with the Statue of Liberty: Tin Can Drives

Tin Can Drives

A Guest Post by Educator Catherine Maryse Anderson

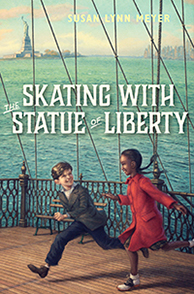

In the final chapter of Skating with the Statue of Liberty, Gustave and September Rose get “into a long line of kids carrying crates and bags full of flattened cans” (p. 285). When they reach the front of the line, they are thanked for “helping our boys overseas.” Like the characters at Battery Park that day, Americans of all ages took part in a massive campaign to support the war effort. Citizens saved and collected metal scraps to “become bombs to defeat the Axis of Evil abroad!”

Gum wrappers; tin foil balls; metal cans; and copper, iron, and tin scraps were all in demand. Children would go from door to door in urban and rural communities asking everyone for contributions. Who didn’t have an old broken rake, a garbage pail lid, or a baking dish to add to the cause? Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops were often leaders of the drives. No one was too young to do their part!

It is not entirely clear how many munitions, bombs, weapons, tanks, planes, or naval destroyers were actually fabricated from these collected metals. Regardless of their physical utility, the drives had an undeniable psychological purpose — gathering scrap metal increased morale. By giving people at home a sense that they were contributing to the war effort, they felt a deeper commitment to the war and the citizens fighting abroad. Recall when September Rose’s grandmother in Skating With the Statue of Liberty pulled down her beloved metal bird sculptures and gave them to September Rose to donate as a “way to bring Dad home” (p. 287). Her son’s safe return was entirely out of her hands, but the successful metal drive propaganda made September Rose’s grandmother feel like she was truly assisting.

In addition to scrap metal, patriotic Americans were encouraged to collect and donate rubber, to conserve fuel by carpooling, and to plant “victory gardens” to feed their families and save resources. Each of these efforts were thought to contribute to the Allies’ chances of victory abroad.

How do current school and home recycling programs help students feel like they are working toward a greater cause? How has the modern school gardening effort taught students about self-sufficiency and healthy eating? What drives have students contributed to in times of crisis? How could classrooms and readers help their communities and the larger world through action?

Sources:

“Scrap Metal and Rubber Drives” from School Library Education Consortium

“Rationing & Scrap Drives” from Farming in the 1940s

“Girl Scouts and WWII” from The National WWII Museum, New Orleans

Image Sources

Image 1: Boy Scouts Gathering Scraps in Lincoln, Nebraska, 1943. Source: Nebraska Studies.

Image 2: WWII Propaganda Poster. Source: Southern Metal Recycling Inc.

Catherine Maryse Anderson has an extensive 15-year background as a public school literacy and humanities teacher in Portland, Maine. She spent two years as a literacy coach for Portland Public Schools and led statewide symposiums on building educator capacity for cross-cultural competency in the classroom from early childcare through college. She was a runner up for the Teaching Tolerance Educator of the Year. Catherine has been involved in ongoing performing arts projects for twenty years and is a published poet and essayist.