I’m the daughter of a child refugee.

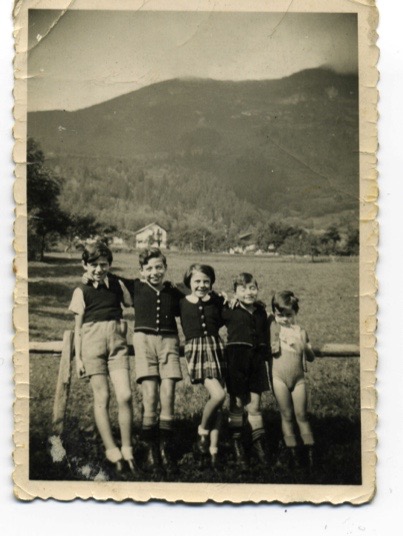

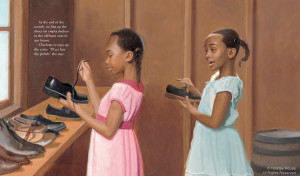

My widowed grandmother came here with her two children in November of 1942, making them among the last Jews to escape from Nazi-occupied France. They had been helped by HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, and the American-Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. My father, Jean-Pierre Meyer, arrived here without shoes. His only pair had been stolen during the train voyage they took through Spain and into Portugal, so he took his first footsteps in America wearing bedroom slippers. Years later, he remembered those slippers: they were navy blue, Scotch plaid.

Millions of European Jews were desperate to get away from the Nazis, and the U.S. wasn’t eager to have them. Jews were a despised religious group. Letting in Jewish refugees could endanger national security, or so officials in the FBI and the State Department claimed. Rather than improving the vetting system, it was easier to turn them away.

Because my grandparents located a distant American relative willing to sign an affidavit on their behalf, my family members were among the lucky few who were finally granted permitted to enter. It was too late for my grandfather. It was very nearly too late for any of them. Eight days after their ship docked in Baltimore, the Nazis occupied the whole of France, taking over Vichy France, where they had been living.

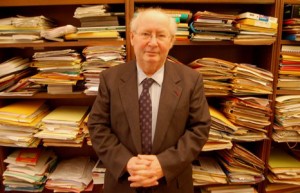

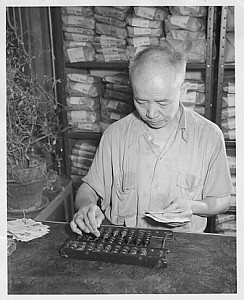

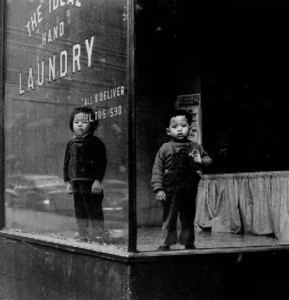

My grandmother found piecework and sewed spangles onto hats in their tiny apartment. My father’s first job in America was as a bicycle delivery boy for a laundry. Thanks to the strong New York public schools, he attended junior high, then Stuyvesant, then CCNY, then Cornell, and became a brilliant and renowned mathematician.

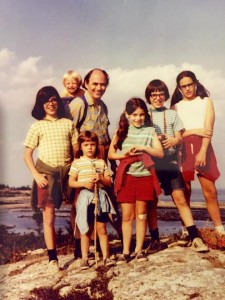

My father had six children. Among us there are a physician, three college and university professors, an investment banker, two writers, and a child psychologist. (Some of us have more than one job.) We’re the parents of ten children. Two among us are married to first-generation immigrants from other countries. Because my father, my aunt, and my grandmother came to the United States, they survived World War II. If they hadn’t been admitted, none of the six of us would be here.

Would this country have been better off without my family?

I think often about all the other desperate Jews, the ones who couldn’t gain entry to America or to any other country, the ones who remained in Europe and were murdered. What talents has the world lost in losing them and their descendants?

What talents and capacities will our country lose now if we stop admitting refugees?

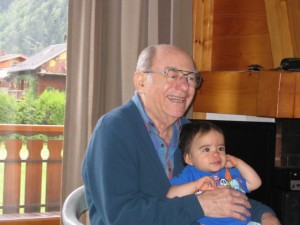

Jean-Pierre Meyer receiving the Seki-Takakazu Prize on behalf of JAMI, the Japan-U.S. Mathematics Institute, 2006.

The six of us kids, like my father, have contributed to the American economy—we have worked hard and paid taxes all our adult lives. We have also contributed in other ways to this country. We pay attention, we vote, and we sometimes engage in political protest. That’s what you do when you love your country and want it to do better. My parents took us kids to Civil Rights rallies and to protests against the Vietnam War. Some of us are protesting now.

We six children of an immigrant father are contributing our intelligence, our work ethic, our awareness of history, our belief in freedom of religion, our passion for education, and our commitment to social justice to this country.

Ours is an American story. Many of you have similar ones.

That is what America is supposed to stand for. That is how America is supposed to work.